- Home

- Alexa Aston

Love and Honor Page 6

Love and Honor Read online

Page 6

Rosalyne watched the man’s face alight. “This is more what I had in mind,” he said eagerly.

“Then you have Rosalyne to thank,” Uncle Temp said. “’Twas her idea to merge the two together.”

“Mmm.” The priest reached for the final sketch and looked at it before resting it on the table. He spread all of them out so he could see each design as he looked from one to the next. Finally, he said, “The last one is obviously the best, though all are thoughtful pieces. It calls to mind everything I desire in the panel, even if it looks to be the most complicated of the lot.”

“I agree,” Uncle Temp stated. “It will take a talented artist to complete this task.”

Courtenay laughed. “And I suppose you are up to this challenge, Parry?”

“I am—along with help from Rosalyne.”

The archbishop turned in her direction. She stiffened her knees to keep herself upright under his scrutiny.

“So, you discussed with your uncle what my panel should include?”

“Aye, your grace. And I will help prepare the wood that the panel will be drawn upon, as well as mix the paints for Uncle.”

“Because you have chosen the most complicated of all the designs, your grace, it will take some weeks to complete,” Uncle Temp said. “Longer than I had first anticipated.”

She knew he tried to give her as much time as possible. Rosalyne didn’t know if she would be skilled enough to complete the panel on her first attempt. Or the tenth, for that matter.

“Shall we say a month from now?” suggested Courtenay. “Surely, that is enough time for an artist of your ability.” His tone did not allow for compromise.

Nodding slightly at her uncle, Templeton assured the priest, “The panel will rest inside Trinity Chapel in a month’s time, your grace.”

“Good.” The archbishop rose. “I look forward to seeing your creation, Master Parry. I suppose you are somewhat like the Almighty in that you are able to create something from nothing.” His face grew stern. “But always remember that every talent, including yours, is God-given and should be used for His glory.”

Both she and her uncle bowed their heads as the archbishop exited the room. Once gone, Uncle Temp hugged her tightly.

“I told you that was the best of all of your drawings. He was delighted.”

Rosalyne shrugged. “I don’t know if Archbishop Courtenay is every truly delighted. He always looks so stern. Being in the same room with him terrifies me.”

“Come. I want to go to Trinity Chapel now and show you exactly where the panel will reside. It may inspire you to see its final resting place.”

She rolled up all of the sketches and thrust them under her arm. They returned to the front of the cathedral and entered, heading east to where the chapel lay. Not only did Trinity Chapel hold the remains of Thomas Becket but also Edward Plantagenet, the Black Prince, who had been interred within the chapel. It was near where the Black Prince’s remains lay that her uncle stopped.

“The panel will be placed here,” Uncle Temp said.

Rosalyne deliberated over the size of wood she would use for her triptych, ignoring the numerous pilgrims that moved about the chapel. Now that she had seen the space in which the panel would rest, she knew exactly what she wanted.

Turning to her uncle, she said, “I am eager to return home and go through the wood we have. I believe I can use some we already possess.”

Uncle Temp kissed her cheek. “I think I will remain behind for a while and pray over this task you will undertake.”

“Oh, mayhap I should do the same,” she said, feeling guilty that she had not thought to stop and pray for heavenly guidance.

“Go,” he urged. “You will have plenty of time later to make your bargains with God.”

“Bargains?” she asked, unsure of what he meant.

He shrugged. “I think all artists think to barter with God as they work on a piece.” He placed his hands on her shoulders. “There will be times of doubt as you work, Rosalyne. Times you fear to continue. Times you are afraid to stop and consider alternatives. But the Living Christ will guide you in this endeavor.” He smoothed his hand against her hair. “I will see you at home.”

“All right.”

Rosalyne left the cathedral and ventured out into the busy thoroughfare. She was keen to reach home and begin the most important task of her life.

Chapter 5

Edward approached the city of Canterbury after traveling for two days. Before his arrival, he needed to change his clothing, so he turned Sirius off the road and veered into the forest that paralleled the road. It seemed odd not to wear his armor while traveling but he would have nowhere to keep it once he arrived at his destination. He had decided not to wear his usual clothes, for it would distinguish his class and not allow him to pass for the common laborer that he would pretend to be.

Because the king requested that Edward leave immediately, there hadn’t been time to find anyone to make peasant clothing for him, so he’d ridden through the streets of London before his departure and looked at what laundry hung outside drying. It took a while to locate something to accommodate his large height and broad chest but Edward thought his search was worth the effort. What he now donned would look well-worn, as if he’d possessed it for a long time. He needed to look the part for the role he would play.

Fortunately, the Black Death had caused increased movement in England. Before plague struck, decimating the population, workers stayed on the estates where they’d been born for their entire lives. The only people who left were soldiers headed to war or the nobility who either followed the king on his summer progress or returned to their estates upon leaving London. With a reduced working class, laborers found they could leave their birthplace instead of staying in one spot and find work at a wage they wanted. It led to growing cities and even other towns springing up. It would not seem odd for him to turn up in Canterbury because of this.

Edward slipped on the frayed gypon and pants. He was lucky to have convinced the woman he bought the used clothing from to give him an extra set. Of course, he had rewarded her with ample coin in order to claim two changes of clothes. Folding the clothes he had just discarded, he would leave them in the bag attached to Sirius’ saddle. His horse’s fine lines would be another thing that could give him away, so he would stable Sirius outside the city. Only when he had worked the wall for a couple of weeks and observed the behavior of both laborers and the men leading the construction would he return for his horse and change from commoner’s clothes to that of a knight and meet with the men in charge.

He brushed his fingers against his soft hunter green gypon before slipping it into the bag. It had been made for him by his mother. Not only was Merryn de Montfort a healer of some repute but she still enjoyed sewing clothing for her children and grandchildren. Securing his things with the leather strap, he gave Sirius a firm pat.

More than anything, he missed wearing his own boots, which he had left in London with Hal. Once again, Edward would have had nowhere to leave them and their outstanding workmanship and spurs that he’d received after being awarded his knighthood on the battlefield were more dead giveaways as to his identity. He smiled, thinking of the thoughtful Humphrey Gardyner, who had made it a point to find Edward at court after the lord commander recovered from his battle injuries. Lord Humphrey himself placed the spurs on Edward’s boots. He appreciated the nobleman’s kindness. Few men would have found time to make such a generous gesture.

Edward wished more men at the royal court could be like Lord Humphrey but men such as Gardyner and Geoffrey de Montfort seemed in scarce supply in King Richard’s London. Most courtiers thought only of how they could station themselves to become wealthier and more powerful, with little regard to others. He supposed his Father’s words had proven truthful—that his day at court had passed. The old guard of Edward III’s no longer was welcomed in a court that grew convincingly self-centered by the day.

Mounting Sirius again, Edwa

rd rode a short distance before he could see Canterbury on the horizon. He spotted a blacksmith’s shed and saw a young boy of about six playing alongside a fence next to the road. The boy climbed up and then jumped down. As Edward rode up, the lad froze, his eyes wide as he stared in Edward’s direction.

“Greetings,” he called out. “Is your father nearby? I wish to speak with him.”

“’Tis a fine horse you have there, my lord,” the lad said.

“Oh, I’m no lord,” Edward said humbly, “but I would like to see your father.”

The boy turned away from the fence. “I’ll fetch him.” He ran into the shed.

Moments later, a burly man with muscled arms and a thick chest appeared, a hammer swinging in his hand. His son followed closely behind.

“My boy says you wish to talk, my lord.”

Edward dismounted. “As I told the lad, I am no lord.”

The smithy appraised him. “You may say so but your horse tells a different story. So does your bearing and your speech, despite the mean clothing you wear.”

He winced. It never occurred to him that his speech might give him away. He would need to add to the story he’d invented as he traveled to Canterbury and remedy that.

“The horse was a gift. My father was steward to an earl and he wanted a better life for me. Told me to pay attention and imitate everything about our liege lord that I could, from the way he spoke to the way he walked.” Edward smiled shyly. “I have a gift for mimicry. It pleases me that you thought me highborn.”

The smithy gave him a toothless grin. “’Twas that or to think you had stolen the horse. You didn’t look the thieving type to me.”

Edward laughed heartily. “Nay, I am honest to a fault. At least, that is what my mother always told me. But I have a favor to ask.”

The man grew wary. “What would a stranger wish from me?”

“I will be in Canterbury for a few weeks and would rather keep a horse with these bloodlines out of the city. You yourself noted his fine lines. I would rather Sirius be somewhere away and safe, where he could be cared for. He is rather spoiled for an animal. My fault, I’m afraid, and that of my liege lord before he passed on and the horse came to me for services I’d rendered to him. I have ample coin to pay you. Would you be interested in stabling my mount until I return?”

He glanced to where the boy peered around from behind his father and tried to sweeten his offer. “Your son could help. Sirius loves children.”

“Could we keep him, Father? Just for a little while?” the boy begged.

The blacksmith considered the proposition as he rubbed his bushy beard. “You say you have coin to pay?”

“Aye. Enough to feed and house him.” Edward winked at the boy. “And, hopefully, for someone to brush Sirius and talk to him every day so he won’t feel so lonely without me.”

The man came to a decision. “Aye. We will care for your horse, my son and I.” He extended his hand. “I am John. This is Will.”

“Short for William,” the boy said. “Mother named me. But she lives with the angels now.”

“I am sorry to hear that,” Edward said. “You must miss her very much. But I’ll wager she looks down upon you from Heaven and watches over you every day.”

“That’s what Father says,” the boy proclaimed.

“Then your father is a wise man.”

The blacksmith said, “We were about to stop and eat our noon meal. Would you care to join us?”

“That would be most kind of you, John. And I am Edward. Edward Munn. Most pleased to meet you both.”

He’d already decided he could not use the de Montfort name, with it being one of the oldest, most noble in England.

“Bring Sirius into the shed. You can rub him down and give him some oats. I’ll prepare something for us to eat.”

“Can I stay with Edward, Father?” Will begged. “He can show me how to brush Sirius.”

His father ruffled Will’s hair. “You may. But do everything Edward says.”

“I will!”

Will led him and Sirius behind the shed to an enclosed structure.

“This is where Father shoes horses. Sirius can stay here.”

Edward removed the horse’s saddle and the small bag that contained his own clothing and the extra set he’d purchased from the London fish wife. He decided he would take the satchel with him instead of leaving it behind. Though John seemed a good man, it wouldn’t do for him to become curious and go through Edward’s things.

“Let me tell you about everything Sirius wears and why he does so.”

He passed a pleasant half-hour with the boy, discussing the horse’s equipment and how to care for both it and the animal. Edward demonstrated how to brush Sirius and gave Will a chance to try his hand at it.

“Talk to him the entire time you brush him,” Edward suggested. “He likes that.”

Will looked puzzled. “What do I say to him?”

“Just speak to him as if he were your friend, for that’s what a horse can be. And be sure to scratch here, between his ears. Sirius likes that most of all.”

After they finished, Will brought him inside a one-room cottage. John gestured for them to be seated and they ate a simple meal together. Edward thought of the rich foods eaten at court and how these two would be happy with a few morsels of court leftovers.

As they ate, Edward asked John about construction on the wall.

“Been going on for some time. It creates steady work for those men who come to Canterbury, which is a good thing.”

“Who leads the construction?” Edward asked, though he already knew. He wished to draw out what he could from the smithy. Local gossip would be something to consider during his time in Canterbury.

“The Crown appointed Lord Botulf to be in charge.” John shrugged. “From what I hear, he only goes to the site on occasion. The actual work itself is in the hands of Perceval Rawlin. He is head of all the crews spread throughout the wall and decides who does what.”

“What do you think of him?”

John grew thoughtful. “I have not met the man in person but I know others who have. Even some who have worked under his direction.”

“And?” Edward thought John was being evasive.

“He’s a bloody bastard,” the blacksmith said. “Deceitful. Corrupt. Why do you ask?”

“I was curious. I’ve heard of the work on the Canterbury walls and thought it had been going on for far too long. Mayhap they need someone else in charge.”

“That won’t happen anytime soon. Not with Rawlin lining his own pockets, not to mention Lord Botulf’s. The great lord seems to look the other way. Most venture to guess that Rawlin gives at least half of his profit to Lord Botulf, which guarantees no questions are asked.” John paused. “But who am I to say? I’m but a humble smithy.”

They finished eating and Edward told John he would be happy if the blacksmith chose to exercise Sirius each day.

“For such a large horse, he’s gentle as a lamb. You would have no trouble riding him if you wish to do so.”

“I may.” John stroked his beard. “I haven’t ridden in some time but I would love to be on the back of a magnificent beast such as Sirius.”

“Then feel free to do so. Take young Will with you.” Edward winked at the boy. “I think he might like that.”

He gave John several coins for the horse’s care and promised more upon his return. Saying his goodbyes, Edward slung the bag over his shoulder as he stepped out into the road and turned toward Canterbury. It felt good to stretch his legs after a couple of long days in the saddle.

A short time later, Edward entered through the city’s gates and decided to walk the streets for a bit. He wanted to familiarize himself with Canterbury and would need to find a place to sleep. He wondered if someone in his position would stay at an inn or even eat there, or if that would be too much coin for a day laborer. He would ponder that as he walked the city.

The main thoroughfare teemed with peop

le that afternoon, much as London did. Edward passed cottages, stalls, and street vendors selling their wares. Though he’d already eaten, the meal hadn’t filled his belly and the smell of meat pies enticed him enough to purchase one and down it in a few, swift bites.

Edward ventured down side streets and then wound back around to the main road that cut through the city. More than anything, he was eager to see the cathedral, which was said to rival any structure in London. As he drew closer, the church did not disappoint. Its majestic beauty nearly took his breath away. He entered and wandered about the main church, soaking up its grandeur. He knelt and said a quick prayer, hoping all in his family were well and that he would accomplish his mission in Canterbury to the best of his ability.

After that, he headed toward Trinity Chapel, where he wished to pay his respects to the Black Prince. Edward had grown up hearing tales about Edward of Woodstock from his father and Raynor. Both men had fought under the Plantagenet prince during the wars in France. Geoffrey de Montfort had stressed to his three sons that not only was the Black Prince a brilliant military strategist and commander but he was one of the best men that ever walked the earth. The Black Prince was known for his generosity as much as his leadership and Geoffrey had emphasized to his sons that both were equally important in life.

Multitudes of pilgrims milled about the chapel, most making their way toward the front. Edward assumed that was where Thomas Becket’s shrine lay. He looked around and spotted what had to be the place where the Black Prince was interred. As he approached, he saw a man close to his father’s age standing nearby.

But it was the woman next to him that drew Edward’s interest.

The candlelight of the chapel bathed her golden hair in warm, rich tones. He longed to reach out and run his fingers through her tresses.

That gave him pause. He hadn’t a romantic bone in his body, unlike Hal, who could wax poetic without thought. Yet everything about this woman made him long to speak to her. She was petite in height, with small, round breasts and an even smaller waist. Her fair skin glowed in the candlelight. He studied her profile a moment and liked the pert, upturned nose. He only wished he could see her eyes as she looked at the wall in concentration.

Medieval Wolfe Boxed Set: A De Wolfe Connected World Collection of Victorian and Medieval Tales

Medieval Wolfe Boxed Set: A De Wolfe Connected World Collection of Victorian and Medieval Tales Dragonblade Holiday Bundle: A Historical Romance Collection

Dragonblade Holiday Bundle: A Historical Romance Collection Season of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 11)

Season of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 11) Hollywood Flirt: Hollywood Name Game Book 2

Hollywood Flirt: Hollywood Name Game Book 2 Song of the Heart (Medieval Runaway Wives Book 1)

Song of the Heart (Medieval Runaway Wives Book 1) Hollywood Enigma: Hollywood Name Game Book 5

Hollywood Enigma: Hollywood Name Game Book 5 The Heir (The King's Cousins Book 2)

The Heir (The King's Cousins Book 2) Hollywood Player: Hollywood Name Game Book 3

Hollywood Player: Hollywood Name Game Book 3 Hollywood Heartbreaker: Hollywood Name Game Book 1

Hollywood Heartbreaker: Hollywood Name Game Book 1 Knights of Honor Books 1-10: A Medieval Romance Series Bundle

Knights of Honor Books 1-10: A Medieval Romance Series Bundle Journey to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 4)

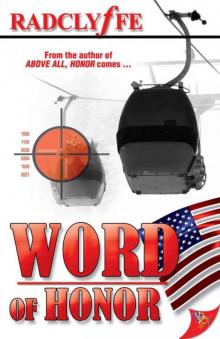

Journey to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 4) Word of Honor

Word of Honor Word of Honor (Knights of Honor Series Book 1)

Word of Honor (Knights of Honor Series Book 1) Suddenly a St. Clair (The St. Clairs Book 5)

Suddenly a St. Clair (The St. Clairs Book 5) Rise of de Wolfe

Rise of de Wolfe Gift of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 8)

Gift of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 8) Marked By Honor (Knights of Honor Series Book 2)

Marked By Honor (Knights of Honor Series Book 2) Journey to Honor

Journey to Honor Gift of Honor

Gift of Honor Love and Honor (Knights of Honor Book 7)

Love and Honor (Knights of Honor Book 7) Bold in Honor (Knights of Honor Book 6)

Bold in Honor (Knights of Honor Book 6) Love and Honor

Love and Honor Path to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 9)

Path to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 9) Bold in Honor

Bold in Honor Return to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 10)

Return to Honor (Knights of Honor Book 10) Heart of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 5)

Heart of Honor (Knights of Honor Book 5) Marked By Honor

Marked By Honor World of de Wolfe Pack: Rise of de Wolfe (Kindle Worlds Novella)

World of de Wolfe Pack: Rise of de Wolfe (Kindle Worlds Novella)